Featuring 165 works – including masks and costumes as well as paintings, musical instruments and songbooks – from the collection of the National Noh Theatre, Tokyo and the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan, Theatre of dreams, theatre of play is the first comprehensive exhibition of the rich material culture of no and kyogen theatre to be shown in Australia.

Featuring 165 works – including masks and costumes as well as paintings, musical instruments and songbooks – from the collection of the National Noh Theatre, Tokyo and the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan, Theatre of dreams, theatre of play is the first comprehensive exhibition of the rich material culture of no and kyogen theatre to be shown in Australia.

With a history spanning over 600 years, no (meaning ‘skill’ or ‘talent’, also spelled ‘noh’) is not only Japan’s oldest continuous performing art tradition but also one of the world’s most ancient theatre forms. Its roots trace back to ritual dances offered at agricultural festivals and entertainments presented by travelling troupes of performers at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines on auspicious occasions.

In the 14th century, Kan’ami Kiyotsugu (1333–84) and his son, the celebrated actor, playwright and theoretician Zeami Motokiyo (c1363-c1443), consolidated these into a sophisticated dramatic art that attracted official patrons and became an integral part of the social elite’s culture.

Often referred to as ‘Japanese opera’, no is a ‘total theatre’ combining drama, music and dance elements that are performed on a highly abstracted stage. A typical program encompasses various no plays – symbolic dramas with a graceful aesthetic that is best expressed through the word yogen (‘elegant, refined, and elusive beauty’). These are interspersed by kyogen skits – spoken drama based on laughter and comedy.

“Although no and kyogen are undoubtedly most appreciated in performance onstage, the enigmatic beauty of the masks and the dazzling splendour of the costumes, along with instruments, paintings and woodblock prints in this exhibition, offer an alternative way to appreciate this time-honoured dramatic art,” said Dr Khanh Trinh, curator of Japanese art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

“These objects are not just functional props but also items of great aesthetic appeal. They were created by master artisans and handed down through influential daimyo households. The patronage by the military nobility also means that no costs and efforts were spared in their production.”

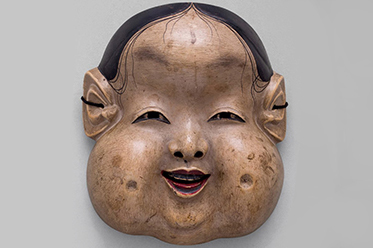

Traditionally, all no and kyogen performers are male, so costumes and masks help identify the characters. Robes, trousers, sashes and headbands are combined according to set rules, with tailoring, pattern, colour and draping used to define gender, social status and psychological state.

There are over 200 types of no masks and about 20 different types of kyogen masks known today. The former include male and female characters, from old men to demons. Most of the latter depict non-human characters such as deities, ghosts and the spirits of animals and plants.

Referred to as ‘omote’ (‘face’), no masks go far beyond the limits of make-up and are thought to be imbued with spiritual power. They do not have individualistic features and generally show a neutral expression. However, they are far from static. A skilled actor can create a great variety of emotions with minute movements of his head.

Theatre of dreams, theatre of play: no and kyogen in Japan

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Art Gallery Road, The Domain (Sydney)

Exhibition continues to 14 September 2014

Entry fees apply

Due to the fragile nature of the works, the exhibition will be closed 28 – 30 July for conservation purposes. For more information, visit: www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au for details.

Image: Kyogen mask Oto, Edo period, 18th century National Noh Theatre