Stephen Sondheim died suddenly on November 26, 2021. Of course, we all knew that he was 91 years of age! And of course, we all knew that one day, like all of us, he would die! But nothing really prepares you for the death of a much-loved musical icon and master.

Stephen Sondheim died suddenly on November 26, 2021. Of course, we all knew that he was 91 years of age! And of course, we all knew that one day, like all of us, he would die! But nothing really prepares you for the death of a much-loved musical icon and master.

News of his passing generated world-wide tributes from artists and fans including Andrew Lloyd Webber, Paul McCartney, Barbra Streisand, Hugh Jackman, Steven Spielberg among many others.

Mandy Patinkin, a major interpreter of his work, lamented, “The guy who wrote my prayers has died. His words were my Torah. Sondheim wrote what he wished for himself and the world at large.”

Hillary Clinton tweeted, “A peerless composer and lyricist, Stephen Sondheim stirred our souls, broadened our imaginations, and reminded us that no one is alone. He changed the theatre – and our culture – with his craft, his humour, and his heart. Everybody rise!”

Others quoted his own lyrics to pay tribute to him, “Sometimes people leave you / halfway through the wood / Do not let it grieve you / No one leaves for good.” Or the line from Sunday in the Park with George, “Look at all the things you’ve done for me / Opened up my eyes / taught me how to see / Notice every tree / Understand the light.”

Stephen Sondheim took musical theatre to a higher intellectual level transcending the standard and popular musicals of the first half of the 20th century, many of them brimming with kitsch and saccharine. Many of these musicals had loose, sometimes ridiculous, storylines with a number of songs inserted in.

Sondheim created shows that were character based and with strong plot development. A song, he once said, must be pivotal in moving both the character and the storyline forward. His work was multi-layered and rich in meaning and realism. He was both an exceptional composer, wordsmith and lyricist and he left behind an extraordinary body of work.

His songs powerfully expressed, not just the joys and the emotionality of the characters but also their flaws, paradoxes and complexities. “It’s the rumblings beneath the surface that interest me the most” he said. He was described as the Shakespeare of Musical Theatre. He liked exploring unknown territory and changing styles in his musicals.

His topics ranged from Ziegfeld Follies, Assassins of U.S. presidents, intertwined fairy tale fables, a story inspired by Georges Seurat’s famous painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, and many other illuminations and meditations on life, love and human aspirations.

There is also his powerful and heartfelt adaptation of Ettore Scola’s 1981 Italian film Passione d’Amore which explores the complexities of love in many of its unrequited, obsessive, unpredictable and uncertain possibilities and machinations.

Some of his songs such as Send in the Clowns have entered the popular lexicon as an abbreviated shorthand to suggest human folly or people behaving badly. Similarly, Finishing the Hat is often used as shorthand to indicate people moving on, completing a prized project or leaving a relationship.

I’m Still Here has become a showbusiness anthem for survival and resilience. The satirical phrase “Does anyone still wear a hat?” from the song The Ladies Who Lunch, is often used as mockery of pretension and pomposity.

His first big success was as a lyricist for West Side Story (1957) and Gypsy (1959), projects he initially didn’t want to take on because he wanted to compose the music as well. But on advice from his mentor Oscar Hammerstein, he agreed to pen the lyrics for what became two classic musicals of that era.

Thereafter he insisted on writing both the lyrics and music for his shows. These included A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962), Company (1970), Follies (1971), A Little Night Music (1973), Sweeney Todd (1979), Sunday in the Park with George (1984), Into the Woods (1987), Assassins (1991), Passion (1994) and many others.

In the month before his death, he told Stephen Colbert on the Late Show that he just had a reading of his new musical Square One and he was hoping that it would be staged in 2022. It was later revealed that Nathan Lane and Bernadette Peters were involved in the reading. An earlier reading and workshop was held in 2016.

It is a collaboration with playwright David Ives and based on two films of the surrealist Spanish director Luis Buñuel, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) and The Exterminating Angel (1962).

Shortly before his death Sondheim told the New York Times, “The first act is a group of people trying to find a place to have dinner, and they run into all kinds of strange and surreal things, and in the second act, they find a place to have dinner, but they can’t get out.”

Since his death there has been wide speculation about whether the public might ever be able to hear this new work either in concert form or as a concept album. Or alternatively, whether the executors of Sondheim’s music might appoint a trusted and faithful composer to work with David Ives to complete any unfinished sections.

Sondheim’s shows were not always hits. Merrily We Roll Along closed after a run of 16 performances, Anyone Can Whistle only managed 9 and Assassins ended after 73 performances. But he persisted with his own unique style and vision exploring unusual storylines and unconventional themes.

In 1995 he told Charles Osgood on CBS, “I mean, an awful lot of people have gone historically to musicals to ‘forget their troubles, come on, get happy.’ I’m not interested in that. I’m not interested in making people unhappy, but I’m not interested in not looking at life.”

In “looking at life” he sought to show the ways in which characters have to face their mistakes, delusions, fears and dilemmas. Nothing was simply black or white, good or bad, right or wrong but rather shaped by our own desires for love, revenge, belonging and happiness.

In No One Is Alone we are told, “Witches can be right / Giants can be good / You decide what’s right / you decide what’s good.” And in Sunday in the Park with George, he tells us, “Pretty isn’t beautiful / Pretty is what changes / What the eye arranges / Is what is beautiful.”

His musical range varied widely in styles and changed with each new show. From torch songs, waltzes, ballads, to laments and more. His choral pieces, parodies and pastiches, comic ditties, military marches, and other songs infused with Viennese operetta and operatic overtones, illuminated his expansive and innovative breadth as a composer.

In his book Finishing the Hat, he sums up his modus operandi for song writing as, “Content Dictates Form, Less is More, God is in the Details, all in the service of Clarity, without which nothing matters.”

Sondheim’s musicals mean many different things to different people. What stands out in many of his shows is a sense of ambivalence and ambiguity in the ways people experience the world. Nothing is as it outwardly appears. You can love someone, care for them, even be married to them and yet feel unhappy or trapped in your relationship with them.

It is this ambivalence that Sondheim evoked in many of his songs. For example, in Could I Leave You? from Follies – a disillusioned Phyllis sings to her husband, “Leave you? Leave you? / How could I leave you? / Tell me, how could I leave when I left long ago.”

Similarly, in Company the song Sorry-Grateful reveals the uncertainty and ambivalence the characters feel about their marriages. “Good things get better / Bad get worse / Wait, I think I meant that in reverse.” followed by, “You’re sorry-grateful / Regretful-happy / Why look for answers / Where none occur / You’ll always be / What you always were / Which has nothing to do with / All to do with her.”

While many theatre audiences know his musicals there remains a largely unexplored body of work outside his main musicals. For the movie Reds he wrote the exquisite Goodbye For Now – a simply worded ballad that is tinged with a sense of tenderness and farewell. He wrote five songs for the movie Dick Tracy, including Sooner or Later, sung by Madonna, which won him the Academy Award in 1991 for Best Original Song.

His comically splendid risqué song I Never Do Anything Twice sung by a madam in a brothel in the movie The Seven Percent Solution exhibits his clever wordplay and rhyming skills, “Once, yes, once for a lark / Twice, though, loses the spark / As I said to the Abbot / “I’ll get in the habit / But not in the habit” / You’ve my highest regard / And I know that it’s hard / Still, no matter the vice / I never do anything twice.”

Evening Primrose – a 1966 television movie, focuses on a poet who takes refuge in a department store only to discover a group of mannequins come to life when the store closes each night. The poet falls in love with Ella who, like all the other mannequins, had been hiding there.

Sondheim gives the couple an enthralling duet Take Me to the World followed by the yearning retrospective song I Remember, which starts with “I remember sky / It was blue as ink / Or at least I think” and ends with,

I remember days

Or at least I try

But as years go by

They’re sort of haze

And the bluest ink

Isn’t really sky

And at times I think

I would gladly die

For a day of sky

Follies (1971) is a homage to the musical revues of the 1920s and 1930s and contains many of his popular songs such as Losing My Mind and In Buddy’s Eyes. Not many people, apart from Sondheim afficionados, know the song Too Many Mornings but it is regarded as one of the great duets in all of musical theatre.

It tells the story of two older people who were lovers in their early adult years and are now married (unhappily) to different people. They meet up at a cast reunion and in a spare moment, amidst the hustle and bustle and mingling of the crowd, Ben finally reveals to Sally his true feelings, “Too many mornings / Wishing that the room might be filled with you / Morning to morning / Turning into days / All the days that I thought would never end / All the nights with another day to spend.”

He was a mentor to Lin Manuel Miranda, the late Jonathon Larson who wrote the musical Rent and a generous and encouraging mentor to many aspiring artists. He was also protective, some would say over-protective, of his work. Many a director or performer would be rebuffed by substituting or omitting a lyric or changing a sequence from a show.

Patti LuPone, one of his biggest stars, recently told the MSNBC network that he was a demanding taskmaster, “I have gotten some very harsh notes from Steve that always improved me but were hard to take because they were quite to the point … and sometimes insulting but he made me a better singer. He made me a better actor. It was an achievement if you did it accurately, if you said the right words and if you sang the right notes. It was an achievement because it wasn’t easy to do.”

Throughout his career Sondheim tried to compartmentalise his public persona from his private self. Patti LuPone described him as a complicated and deeply emotional man. He often asserted that none of his songs and storylines were biographical. He noted, “My personal life and my artistic life do not interfere with each other.”

While one might accept that at an explicit level, many do ponder the relationship between biography and creative output in the themes, nuances and ideas that are given expression and brought to life in his work. It is difficult to conceive that an artist’s life experiences do not influence their work in some implicit way.

He was never in a permanent romantic relationship until he was in his 60s. And he carried within himself the wounded boy from his childhood. His parents separated when he was 10 and went through an acrimonious divorce. He also endured an abusive relationship with his mother. She once sent him a hand-delivered letter that said “My only regret I have in life is giving you birth.”

Fortunately, for him, he found a loving second family in Oscar Hammerstein and his Australian wife Dorothy. Hammerstein became a father figure and mentor for the young Sondheim. He often said that if Hammerstein were a geologist, he would have become one too.

Or perhaps, like Lorenz Hart, the great song writer of the first half of the 20th century, he put into his songs much of what was elusive and unattainable in his personal life. Hence the angst of Being Alive, which is essentially an epiphany of someone acutely aware that they are alone and yearning for love and connection. “Somebody hold me too close / Somebody hurt me too deep / Somebody sit in my chair / And ruin my sleep / And make me aware / Of being alive / Being alive.”

In songs like Anyone Can Whistle – a vulnerability and poignancy of someone who is unable to love is expressed in the metaphor of a whistle: “What’s hard is simple / What’s natural comes hard / Maybe you could show me / How to let go / Lower my guard / Learn to be free / Maybe if you whistle / Whistle for me.”

On news of his death a heartbroken Lin Manuel Miranda tweeted, “Future historians: Stephen Sondheim was real. Yes, he wrote Tony & Maria AND Sweeney Todd AND Bobby AND George & Dot AND Fosca AND countless more. Some may theorize Shakespeare’s works were by committee but Steve was real & he was here & he laughed SO loud at shows & we loved him.”

The star of the current Broadway production of Company, Katrina Lenk, mused, “He’s still here, and yet he’s not here – it’s a very Sondheim thing to have two very contradictory ideas existing in the same space.”

At the conclusion of his 80th birthday celebrations at New York’s Avery Fisher Hall in 2010 he told the audience, “First you’re young, then you’re middle aged, then you’re wonderful. This is wonderful.” Stephen Sondheim took us on an uncharted journey of musical gems and masterpieces for over 70 years of unsurpassed creativity and innovation.

As the philosopher John Ruskin noted, “All that is good in art is the expression of one soul talking to another.” His 1964 musical Anyone Can Whistle provides a fitting epitaph for the dazzling and magnificent body of work he has left us with – and an enduring legacy that will be forever etched in our hearts and memories.

It was marvellous to know you.

And it’s never really through.

Crazy business this life we live in,

Can’t complain about the time we’re given –

With so little to be sure of in this world.

Thanks for everything we did,

Everything that’s past,

Everything’s that’s over,

Too fast.

None of it was wasted.

All of it will last.

The Legacy of Stephen Sondheim by Peter Khoury

Peter Khoury is a writer and academic. He was a regular contributor to The Sondheim Review and Everything Sondheim magazines.

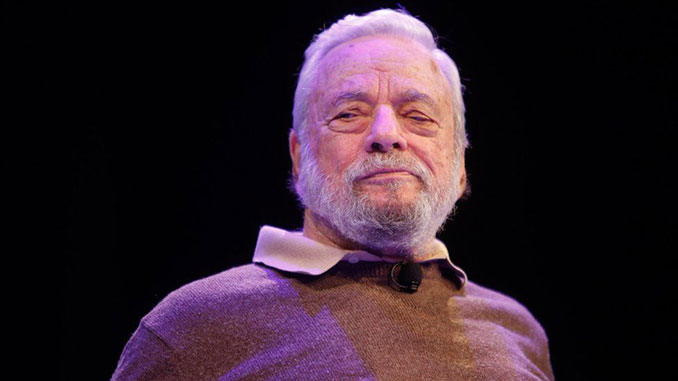

Image: Stephen Sonheim (Getty Images)