There’s a big difference between a biennale and a biennial. Although both words simply mean an event that’s held every two years, in an art world context they have very different connotations.

There’s a big difference between a biennale and a biennial. Although both words simply mean an event that’s held every two years, in an art world context they have very different connotations.

The former is the posh Italian word for a large-scale, high profile exhibition that’s preferably staged on an island such as in Venice, Italy – or even Cockatoo Island, Sydney. They have artistic directors drawn from a rarefied field of international curators and they come wrapped up in big ideas and a conceptual bow of intellectual credibility.

The latter, by contrast is a much more modest affair – in the art world the biennial is basically admitting that the exhibition – for that is what it is – eschews the razzamatazz of the biennale and has a much more modest aim, to simply create an bi-annual exhibition that has more credibility because of its modesty.

In that context, the Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial has an interesting history. Between 1993 and 2012, it ran as a prize worth A$30,000 and for a time was staged alongside The Archibald Prize for Portraiture. It attracted entries from across the country and usually featured dozens of finalists. But in 2012, the Art Gallery of NSW decided to reinvent the Dobell as a curated exhibition.

It always seemed to me that in its final years the Dobell was repeating itself. While there was some welcome variation in the kinds of work being selected, it was a show of artists producing work that aspired to credibility that’s bestowed upon the art of drawing. Where was the raw, untutored stuff that was being produced out there in the world of artist run galleries? Where were the outer limits of the practice in performance or video?

Drawing Out, the first Biennial in 2014, was a much more modest affair than the former prize, featuring the work of just ten artists. Disappointingly the show included names familiar from the Dobell prize era but there were some pieces that challenged the very concept of what constitutes a drawing, works such as Gosia Wlodarczak’s performance drawing on the window of the gallery, Anna Pollack’s short video animation and Mary Tonkin’s 14-metre long panorama. Alongside the more traditional works, the 2014 Dobell had both substance and breadth.

So I went off to see Close to home: a celebration of contemporary drawing in Australia not expecting a massive biennale but a substantial and consequential biennial. There are just six artists in the show. Six. And all of them have exhibited work at the Art Gallery of NSW before. Three are from Sydney, two from Melbourne, one from the NT.

The artist Noel McKenna, whose work I love, has paintings and drawings in the gallery’s collection, as are paintings and sculptures by Nyapanyapa Yunupingu. An unkind person might take the show’s title as the curator brief – keep it small and cheap.

Sequestered in a small downstairs gallery space adjacent to Julian Rosenfeldt’s Manifesto video installation – a star-studded, feature-film level production and intellectual wank-fest that sprawls through three galleries – the Dobell Biennial looks modest in the extreme.

As much as I detest art critics who spend more time rubbishing the management of an art gallery rather than actually engaging with the art, this context is crucial in understanding the stakes of the art of drawing in the contemporary art world. As much as I have championed video art in the past, I would never have dreamed that a worthy show like the Dobell would be given such short shrift when it came to gallery space and resources.

You might even go so far as to argue that drawing is being shunted out in favour of the smoke and mirrors of new media, but I’ll leave that argument for another time. Happily, the quality of the work in Close to Home manages to shoulder much of the expectation of a show once described as “the most important” exhibition of its kind in Australia.

McKenna’s Animals I have known (2015) is another of the artist’s signature works that mix text and drawing, here a chart of dogs he has owned and other creatures he has encountered over the years such as possums in the trees around his Rose Bay home, and chickens in a friend’s yard in Darlinghurst. As curator Anne Ryan notes, the work – a collection of related drawings and the chart – is both acutely observational but also emotional, and utterly beguiling if you happen to like dogs, as McKenna’s economical line captures perfectly their attitude and profile.

An interesting connection between the nature of representation and the art of drawing connects a number of other works too. Nyapanyapa Yunupingu’s drawings are notable not only for their use of fibre-tipped pen, natural pigments, clay and acrylics, but their eschewal of strict narrative for the formal qualities of mark making.

The dense crosshatch abstract form of Larrani (2014) is an optically fascinating field of lines while the larger multi-panel work Djorra (paper) 1 (2014) relates a story of when the artist was gored by a wild buffalo. Where in one drawing the line is about the simple act of mark making, in the other it has a narrative quality.

Catherine O’Donnell’s massive Inhabited Space (2015-16) is a wall drawing that depicts the simple lines of the suburban fibro house; its windows and screen doors hyper detailed charcoal on paper drawings. Together, the schematic outline and the detail coalesce, and like Yunupingu’s drawings, float between abstraction and figuration.

With that knowledge the viewer scrutinizes the faces to see some trace of that condition being somehow represented in the drawing, but the realisation that these are drawings, not documentary photographs, only becomes obvious the longer you look. Lewer’s avoidance of expressionist illustration only makes the images more powerful.

Richard Lewer’s nine drawing series have titles that describe states of mind – Depression is like quicksand, you have to avoid panic to escape (2015), The distance is not what you measure, it’s what you create (2015), I’m fine, I’m just tired (2015) among them – and accompany head-and-shoulders portraits of friends and acquaintances who have experienced anxiety and depression.

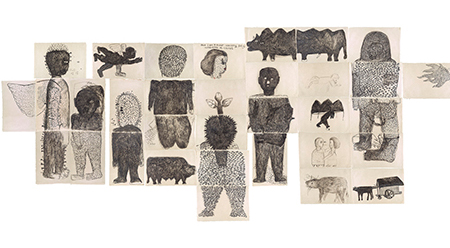

Australian-Indonesian artist Jumaadi’s work explores another kind of subjectivity – his own, and the arrangement of drawings are a kind of diary of thoughts, feelings, and dreams, given form in monstrous figures mixed with odd observations – a bullock pulling a wagon, doll-like figures in embrace. Despite their darkness, there’s a beauty in their ambiguity.

The sixth artist in the Dobell Biennial is Maria Kontis whose work are painstakingly rendered pastel on paper drawings that reproduce certain elements of images from found photographs.

Drawn at full scale but set adrift on much larger sheets of framed paper, the works have the studious air of a post photography project, finding in works such as Edmund Floating (2014) or Him or Me (2015) obscure details that are emphasised to enhance the ambiguous nature of the images. There’s stillness in these works that draw their power in part from the found image, but there’s also an undeniable aesthetic power in Kontis’s hand.

Despite the modest state of the show, and the limited number of works, Ryan should be acknowledged for bringing together such an impressive exhibition. Although biennial might suggest a bigger scale, it’s not limited in scope.

The Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial 2016: Close to home: a celebration of contemporary drawing in Australia is showing at the AGNSW until 11 December 2016. Admission is free.

The Dobell Drawing Biennial: modestly staged, impressively rendered

Andrew Frost, Lecturer in Media

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Image: Jumaadi, Halfway to the light, halfway through the night, 2010-14 – photo by Felicity Jenkins ©