Chances are you have seen some of William Yang’s photographs in the major state and national galleries of Australia. Perhaps you have seen his documentary films, aired on television, or performances in galleries, where he uses his photographs to illustrate monologue presentations. Or you may have stumbled across his intimate images of the gay, lesbian and transgender world.

Chances are you have seen some of William Yang’s photographs in the major state and national galleries of Australia. Perhaps you have seen his documentary films, aired on television, or performances in galleries, where he uses his photographs to illustrate monologue presentations. Or you may have stumbled across his intimate images of the gay, lesbian and transgender world.

Whichever side of Yang’s work you may know, the release of his new book, William Yang : Stories of Love and Death (2016) (from an exhibition of the same name) gives us the chance to see it in a new light.

Since his first solo exhibition in 1977, the prolific Queensland-born photographer has created portraits of his family, drawing on his Chinese heritage and Australian migration experience. Longhand text often overlays these images, further developing the story-telling. Yang has also reported on the lively cultural and social scene of Sydney.

The launch of William Yang: Stories of Love and Death (2016) by Edward Scheer and Helena Grehan, coincides with an exhibition at Stills Gallery in Sydney – Old New Borrowed Blue – and parallel exhibitions atKick Contemporary Arts in Queensland and the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Most of the photographs in the Stills Gallery exhibition are self portraits. We see ancient Chinese costumes; travelogue images of his journeys through China; nostalgic photos of Yang as a young boy and his face superimposed on a foggy Chinese landscape. Some of the photographic text reveals his cheeky humour. Reads one:

I came to Sydney in 1969, I dropped out and grew my hair… I had already taken LSD.

The book charts Yang’s complicated sense of identity as a Chinese man, an Australian man, a gay man and an artist. It also pays homage to the body of images that record the impact of the AIDS virus on the Sydney gay scene. They are full of pathos and grief. So many of Yang’s friends were lost during the 80s and beyond.

The flip-side of Yang’s documentation of death is the joyful celebration of the LGBT Sydney scene: a world of parties, diversity, excess and difference that slides into the slightly debauched.

It is this combination of immigrant identity, sexual awakening and creative imagination that makes Yang a major figure in Australian art and celebrity society. Many art lovers know his images of Sydney figures and the profound images of his Chinese heritage. But there is a depth to his work many of us don’t know.

What the authors of this monograph emphasise is that Yang’s work is not limited to photography. He is also a live performer and filmmaker. Both Scheer and Grehan are professors of performance, maestros of that slippery realm that is not theatre, not visual art but has long been a mysterious lacuna between the two.

Yang’s performances are theatre-like presentations or dramatic monologues. They detail his experiences (often with humour) and are accompanied by slide projections of his photographs. This style of performative art is unusual. It sits somewhere between documentary, memoir and moving image. The authors of the book argue that this new form of performance, which began as a way of animating the photographs, gives them,

another life, another audience, allowing the work to endure and to evolve, and therefore saving the photographs from the deathly touch of the archivist’s white cotton glove.

By creating live performances, they note, Yang has managed to re-use the photographs in a different setting – giving them a longer and more animated life. Yang’s story-telling skills are a means of sharing experiences that are common to all humanity – love, pain, connection, death and grief.

While Yang, throughout his career, has made his art a method of discovering his own identity, he has managed to chart a large slice of the Sydney social world too. What were once photographs of the cultural elite are now available as a vital resource: the writer Patrick White, designer Jenny Kee, artist Brett Whiteley and his daughter Arkie. Yang’s subjects are not, however, just the glitterati, but the forgotten and the forsaken too.

The breadth of research in Scheer and Grehan’s book is scholarly, but the writing is ideas-driven. This is the task of the art writer: to write in tandem with the opus of work, creating a text that is informed, spirited, intimate and thorough.

And, then, to say something new. The pair have focused on this transference of form across media – photographs, film, performance, documentary – and explored how Yang’s “carnivalesque” (the experimental way he represents himself, outside conventional portraiture) has become part of how we all might potentially see ourselves.

Yang’s expressive and performative photographs create a Sydney aesthetic, in harmony with other contemporary photographers such as Nan Goldin, Tracey Moffatt and Simryn Gill.

Why? Because they are frank – whether historical records of Yang’s Chinese descendants or memorials of the gay protest movement – and they are mortal. The photographs chart a moment in the race towards death.

They apprehend death, by documenting life, but they suffer their own mortality as materials that disintegrate over time. So the mortality is infinite. This is what the authors illuminate in their book. The brutality of life. The beauty of death.

Is Australian culture really about mateship and beers at the pub? Partly. But it is also a space where photography has made a significant benefaction to the “face” of Sydney. Yang has been the most influential contributor to that diverse and complex image of a city.

My Queensland is showing at Kick Contemporary Art, QLD until 26 March 2016. William Yang in Public Image, Private Lives can be seen at the Art Gallery of South Australia until 3 July 2016.

Stories of Love and Death: casting a new light on William Yang

Prudence Gibson, Art writer and Tutor, UNSW Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

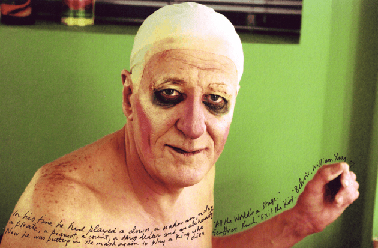

Image: All the World’s a Stage, Geoffrey Rush, Exit the King, Belvoir, 2007 William Yang