Circus has always shamelessly borrowed from other performance forms. It has coopted all types of music to sit alongside its signature brass band sound, so that music and circus are synonymous – although not necessarily thought of as such. This union allows body-based acrobatic performance to create emotional mood and sensory impact.

Circus has always shamelessly borrowed from other performance forms. It has coopted all types of music to sit alongside its signature brass band sound, so that music and circus are synonymous – although not necessarily thought of as such. This union allows body-based acrobatic performance to create emotional mood and sensory impact.

Perhaps mood isn’t what comes immediately to mind for circus. But creating a pleasurable mood has been fundamental to its success. The circus delights and excites, as it induces visceral thrills and anxiety about risky feats.

One of the major innovations of the 40-year-old animal-free circus movement has been the diversification of its hyper-cheerful emotional quality. From the French circus Archaos with its terrifying Mad Max aesthetic and machines to the danced and sung, non-abrasive gentility of the Canadian Cirque du Soleil, circus arts now span a full range of theatrical moods.

Three recent productions in Melbourne combined circus and classical music to foster emotions ranging from amusement to pathos. They worked for the audiences but not completely in favour of each art form. How might performance forms that have evolved separately come together in an artistically coherent way? More crucially, why bring them together?

As well melding circus, opera and symphony music, each production involved an additional performance form: respectively illusionist magic, Commedia dell’Arte and image-based contemporary performance. A delineated form has practical and artistic justifications, as well as informing audiences what to expect.

But blurring the distinctions can also be artistically productive. There’s something magnificent about artists working ‘live’ and in large numbers; playing instruments, singing opera and doing circus feats.

Cirque de la Symphonie and illusion

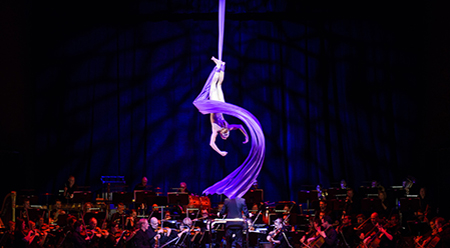

The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra performed in Cirque de la Symphonie in Melbourne’s Hamer Hall concert venue. The strenuous muscular technique behind circus usually remains unseen, camouflaged behind easeful grace, smiles, sequin flashes and the ‘styling’ or held poses between each sequence or trick – all contributing to conventional mood effects.

Does the circus need the orchestra or vice versa, I wondered, to justify the leap in scale from circus band to the high status, full orchestra? After all, an acrobatic act can be artistic and athletically accomplished within low status, gaudy spectacles. The underlying imprint of this populist aesthetic might have been evident in Cirque de la Symphonie, but it delivered virtuoso performances of both circus and music.

Circus is body-based performance with apparatus, which might only be a weight-bearing belt or a special floor mat. Orchestra, too, might be considered body-based performance with instrument equipment. Both forms involve training intensely and repetitively to master the skills.

Highly accomplished solo or duo acts in acrobatic balance, juggling, and illusionist costume change acts, and acts on aerial silks (hanging fabric) and aerial straps were performed in front of the orchestra, which played music by Dvorak, Saint-Saëns, Bizet, de Falla, Khachaturian and others.

There were several stand-alone orchestral pieces by Glinka and Strauss, and at times the music seemed to soar high in beautifully invisible motion. In this union, orchestral solemnity and circus brashness were discarded as the conductor Benjamin Northey began to act like a ringmaster. He was eventually incorporated into an illusion rope trick from which a female illusionist emerged wearing his jacket.

The atmosphere was warmly light-hearted, and the imperative to please an audience still distinguishes much contemporary circus – such as Circus Oz – from other theatrical and dance performance. Cirque de la Symphonie’s familiar formulaic effects were not particularly demanding to watch; the audience clapped each accomplishment like a circus audience even while the orchestra was still playing.

Laughter and Tears and Commedia dell’Arte

A collaboration between the Victorian Opera, Orchestra Victoria and Circus Oz with Dislocate might seem unlikely. But their large production, Laughter and Tears, made opera entertaining like circus in Act I and circus moments heartfelt like opera in Act II.

There are precedents for this opera and circus combination and the production directed by Emil Wolk deserved a full house. It featured accomplished orchestral performance under conductor Richard Mills; strong operatic performances; truly funny clowning; seamless acrobatic action; and lovely aerial movement. The production solved the problem of two completely different art forms by emphasising one in each act. They were linked together by a play-within-a-play structure presented by Commedia dell’Arte stock characters.

Laughter – set in 1938 in Sicily, presented a commedia narrative in acrobatic slapstick. It was accompanied by 23 pieces of 16th to 18th century music from minstrels, to works by Scarlatti, Vinci, Banchieri, Vivaldi, Monteverdi and Gesualdo. Tears – set after World War II in 1945 in Sicily, was the opera Pagliacci by Ruggero Leoncavallo, in which a tragic love triangle among travelling performers is played out during their commedia performance.

The early action soon turned into Circus Oz larrikinism complete with male-to-female cross-dressing. Three men and one woman appeared as stagehand characters in 1930s overalls. Five singers appeared in commedia costumes. The character of Nedda sang from the balcony where she was imprisoned by el Capitano, with her lover, Arlecchino, watching from below.

Act I involved repeated clowning efforts to climb up to the balcony and unite the lovers and culminated in three-person-high shoulder balances executed with seeming ease.

In some hilarious acrobatic sequences, el Capitano’s leg was caught in a collapsing balcony rail and the female stage hand character became the Commedia character, Columbina as she flew up in an aerial harness. Capitano descended to chase the acrobats around the stage brandishing his sword as they somersaulted in and out of windows, and through doorways.

As the male stage hands appeared in the glorious commedia dresses of the singers, the surtitles wittily advised: Health warning: anyone musical, please leave now. Mayhem ensued in familiar Circus Oz style as Nedda escaped with Arlecchino. The mood shifted to wariness as a Mussolini blackshirt announced war, and that “commedia is finished” – a line from the Pagliacci opera.

In Act II’s opera the clown, Canio, murders his unfaithful performer wife, Nedda, and her lover, Silvo, witnessed by the audience crowd created by a large opera chorus.

Nellie Melba famously sang Nedda early in the opera’s history in London, but I questioned this choice. Such repulsive brutal (domestic) violence needs to be challenged by a clear critical perspective in contemporary staging – for example, being framed by stylised freezes in the action.

Il Ritorno and contemporary performance

Circa’s performance, Il Ritorno reinterpreted the narrative of Ulysses returning to Penelope, with contemporary physical theatre and opera by Monteverdi, Grant, Mahler and others. Circa’s intricately choreographed acrobatic movement and operatic music were in contemporary performance style and, even though segments were framed by projected surtitles outlining the basic narrative, this was not a story.

Il Ritorno had seven acrobat performers, three opera singers and three musicians who played violin, accordion and flute, and the piano, harpsichord and cello. It started with slow figures in half-light accompanied by haunting vocal and cello music.

Then acrobatic bodies crumbled and collapsed as if attacked by invisible forces as the performers moved across the stage in hand-stands, somersaults, balances – including two-person and three-person-high shoulder balances – and full body throws and catches. Bodies were hanging, falling, catching and grabbing.

Clearly, the myth suggested boats unable to reach Mediterranean shores and homeless wandering, and the performance conveyed the impression of an epic. Not only was the sorrowful mood completely different from the other two shows, but circus and opera were fully integrated. The acrobats and singers moved across the stage together so that Il Ritorno developed as a theatrically coherent whole.

The sparse poetic classicism was evocatively melancholic, and delivered with a sensibility that was beautiful and yet disturbing. The eerie effect, while masterful in its hint of suffering, may not have pleased the spectators who came wanting more cheerful circus or a more explicit message.

The production had a rhythm in which the performers moved, paused, then moved again. The grey-brown tones in combination with the music and jumbled bodies suggested a medieval world – or perhaps its painting – rather than the sculptural perfection of Ancient Greece.

Alongside the singers, the mobile acrobats seemed more neutral, less personality but more body. The art was in the pauses, holds, and bodily montage imagery refined by Circa director Yaron Lifschitz. This was a director’s text developed with the artists and composer-arranger Quincy Grant.

The body training was unquestionably acrobatic but not straightforward circus as multiple effects blended together. Acrobats worked in pairs momentarily, male with female, male with male, before dissembling and reassembling; a cloud swing appeared but not for a full act. Female performers were lifted or turned or bodily thrown or presented spread-eagle in leg splits on the ground, in a lift, and suspended from trapeze, but they were also the base of a balance. Male performers stood on female chests among multiple variations in the fascinating movement.

Invisible hands seemed to tear at a solo female performer in extreme thrashing, stabbing and writhing until she left, precariously walking on bent toes. Three female acrobats hung from a wide trapeze in slow stretches and held poses, and two held a third performer suspended below. The poses flowed into each other rhythmically like beautiful stanzas of verse.

In the Chorus of Farewell, the acrobats worked impressively in shoulder balances. In one instance, a performer was swung into the arms of a second one, who stood on the shoulders of a third. Three women stood stretching out, fan-like, on top of the shoulders of a male acrobat like an illustration from a Greek vase. At the end, the performers slipped away one by one through a back-lit doorway as if through time and memory.

The coincidence of these three shows happening within a month has drawn public attention to the artistic possibilities of such collaborations. But perhaps the companies might have preferred that they were not competing with each other for audiences. It’s unlikely that this synchronicity could have been foreseen by the producing organisations.

The lead times on the development of such large productions and the scheduling into major venues would have been at least two years, and Circus Oz has been in discussion about an opera circus production for some years. It’s not possible to say whether this type of artistic expression might be attributed to a zeitgeist effect or the myriad of ways in which artists and productions indirectly influence each other.

Cirque de la Symphonie delivered a cheerful enjoyable show with a well-tested audience-pleasing repertoire from both art forms. By interval, however, I wondered if the sensory preference for either music or circus divided spectator attention.

Laughter and Tears aroused more laughter than tears as the comedic narrative of the unfaithful lover was not easily flipped into pity despite some powerful operatic singing. Il Ritorno sought sensory immersion as it evoked a solemn response; that is, it demanded the undivided serious attention of its spectators. While the requirement of work and commitment from an audience might seem an anathema to circus, an intense mood is completely integral to circus artistry.

Sequins and symphonies: how opera ran away with the circus

Peta Tait, Professor of Theatre and Drama, La Trobe University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Image: Cirque de la Symphonie – photo by Daniel Aulsebrook