“As an Indigenous woman, my female body speaks for itself.” – Rebecca Belmore (2007)

“As an Indigenous woman, my female body speaks for itself.” – Rebecca Belmore (2007)

Rebecca Belmore’s corpulent force carries Turbulent Water, Australia’s first solo of the celebrated Lac Seul First Nation (Anishinaabe) artist. Showing at Buxton Contemporary until May, the exhibition broadly positions Belmore’s works: video projections with performance and sculptural elements which nurture Indigenous peoples’ cultural bonds and abrasions.

The exhibition opens with Perimeter (2013), a work conceptualising the junction between intrusive colonial structures and the endurance of Indigenous land. In and out of frame, Belmore walks the landscape, traversing water and stone, wearing a hi-vis vest and holding trailing red flagging tape. Fluro lettering on an adjacent wall to the projection reads, ‘somewhere between a town a mine a reserve is a line.’

Following this subtle but precise introduction, Belmore, in each work, situates her flesh with natural resources as a visible site of cultural power and grief.

The exhibition’s gravitas, Fountain (2005), juxtaposes the artist struggling in a body of water projected against a soft line of showering water. One could stare at Fountain for hours, absorbed into the rhythm of Belmore’s breath and suffocation. But, although liberally spacing five installations across four rooms, Turbulent Water does little to allow the feeling of her work beyond its vibrations.

For instance, both works mentioned above don’t provide seating. Not only strange per accessibility needs but at 22-minutes long Perimeter (2013) loses its slow sensory immersion as people move on, either restless or sore.

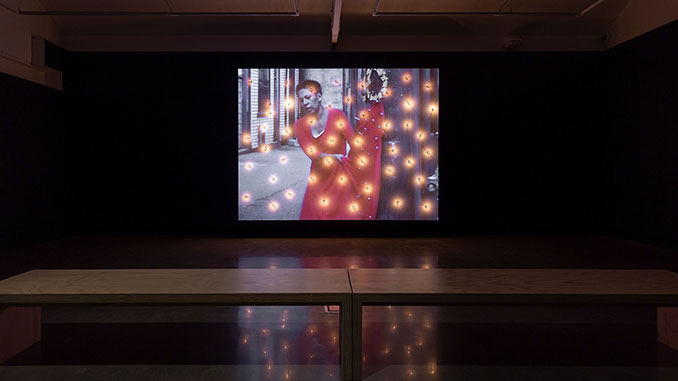

In Named and Unnamed (2007) Belmore’s intentional movements, lighting candles and scrubbing concrete at an intersection, hold the curious viewer’s gaze. Although offering seating, the wall text’s placement in a dark corner hides the context of Belmore’s aim to make the ‘invisible visible.’ It is only through reading it and knowing Belmore screams the names of murdered Indigenous women can the work come into its chilling weight.

Like this, the exhibition design often limits encounters with the urgent messaging driving Belmore’s emotional crux. Apparition (2013), which shows Belmore sitting with her taped mouth among ambient blue light and clouds reminiscent of a Christian heaven, loses out to the larger and louder Fountain in the same room – ironic given its focus on the silencing of Indigenous language.

But focus isn’t necessarily Turbulent Water’s priority: the vague main exhibition statement jumps between keywords like contemporary society to universal truths to the human experience. This catch-all framing of Belmore’s solo forgoes a thoughtful through-line between the installations in favour of thematical breadth.

Such self-evidences in the final room with a collage of 20+ years of Belmore’s video works – a chaotic presentation undermining their individual power and impossible to focus on. With no thought to lighting and hung across from the elevator, this anticlimactic final installation looks like an ugly afterthought. Observance, Buxton’s upstairs exhibition featuring six First Nations female artists, somewhat relieves this abrupt ending to Belmore’s solo.

Curatorial belief in the self-transience of work contributes to the exclusivity of art spaces. Belmore’s deeply effecting works require time and attention (and seating) to transmit empathy and knowledge between the bodies of the audience, art, and artist. Kneading out these boundaries doesn’t need to be heavy-handed: Perimeter’s eleven words of fluorescent text shows that soft yet didactic methods can meaningfully canvas an exhibition.

Rebecca Belmore: Turbulent Water

Buxton Contemporary, corner Dodds Street & Southbank Boulevard, Southbank

Exhibition continues until 8 May 2022

Free entry

For more information, visit: www.buxtoncontemporary.com for details.

Curators: Wanda Nanibush and Angela Goddard

Image: The Named and the Unnamed 2002, Installation view: Rebecca Belmore Turbulent Water, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne 2021–22 Collection: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Courtesy the artist – photo by Christian Capurro

Review: Tahney Fosdike | @tahnsuperdry | tahney.com