On display at the Kerry Packer Civic Gallery – University of South Australia until 30 May 2024, Now Showing… Cinema Architecture in South Australia, highlights the importance picture palaces contributed not only to the lives of those who visited them, but also to main street architecture across the state.

On display at the Kerry Packer Civic Gallery – University of South Australia until 30 May 2024, Now Showing… Cinema Architecture in South Australia, highlights the importance picture palaces contributed not only to the lives of those who visited them, but also to main street architecture across the state.

From suburban cinemas to grand picture palaces in the heart of the city, the buildings designed for showing motion pictures in the twentieth century became centres of entertainment for South Australians.

These were often highly decorated and embodied the glamour of Hollywood in their design. Going to the movies was a popular form of entertainment but also, in the days before television broadcasts, was a way of getting the latest news.

The social aspects of watching a movie together with others in a venue, the cinema snack bar, queuing for tickets, chatting during the intervals, and in some cinemas, the live music from a theatre organ were also part of the experience.

When a member of the public mentioned the fond memories she had of going to the pictures and the glamour of movie theatres of the past, Dr Julie Collins, Curator at the University of South Australia’s Architecture Museum, thought this sounded like a good idea for an exhibition.

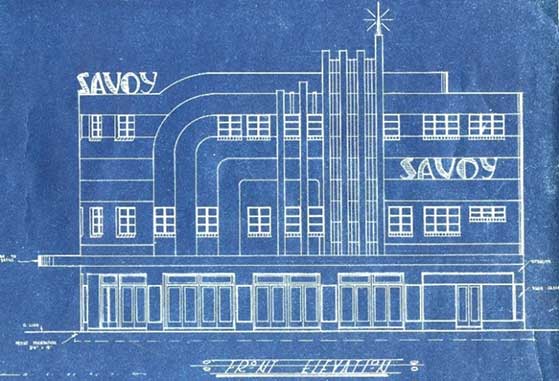

While researching the exhibition with colleagues, Naomi Giles, Dr Susan Lustri and Dr Susan Avey, they uncovered a trove of old architectural plans and photographs of South Australian cinemas in the collections of the Architecture Museum.

“We found blueprints for many of the landmark picture theatres around South Australia, including the Piccadilly at North Adelaide, the Capri at Goodwood and the Victor Ozone at Victor Harbor,” said Dr Collins.

“We found blueprints for many of the landmark picture theatres around South Australia, including the Piccadilly at North Adelaide, the Capri at Goodwood and the Victor Ozone at Victor Harbor,” said Dr Collins.

These architectural drawings and photographs, together with ephemera, scrapbooks, and short films by local picture theatre historian Damian Woodards make up the exhibition.

“While moving picture shows were screened in South Australia from as early as 1896, it was not until the 1920s that this form of entertainment gained mass appeal. During the silent movies’ era, films were accompanied by live music and theatre operators would employ a pianist or small orchestras whose performances were part of the attraction,” said Dr Collins.

Before the emergence of purpose-designed picture theatres, many local town halls and civic facilities showed films in live performance venues, such as the Thebarton Theatre or the Port Lincoln Civic Hall with most suburbs and towns had at least one venue appropriate for cinema entertainment by the end of the 1920.

Following the arrival in Australia in 1928 of motion pictures with synchronised soundtracks, known as – ‘talkies’ – picture theatre design began a new chapter. The 1930s was marked by the uptake of Art Deco and Moderne styles across many building types, but it was in picture theatres that both styles flourished.

Typically, the exteriors featured curved forms, horizontal streamlining, decorative banding, grilles and fins, all illuminated at night in bright lights or neon. Inside, moulded plasterwork, curves, concealed lighting and modern materials such as chrome, as well as wall-to-wall carpet, created dramatic and opulent interiors, giving patrons the experience of a night out.

Typically, the exteriors featured curved forms, horizontal streamlining, decorative banding, grilles and fins, all illuminated at night in bright lights or neon. Inside, moulded plasterwork, curves, concealed lighting and modern materials such as chrome, as well as wall-to-wall carpet, created dramatic and opulent interiors, giving patrons the experience of a night out.

Architects became specialists in the theatre design field with names including Chris A. Smith, Evans, Bruer and Hall, and F. Kenneth Milne prominent among them. International and interstate architects also contributed to the state’s picture theatre designs too, even some from New York designed the MGM Metro Theatre which formerly stood on Hindley Street.

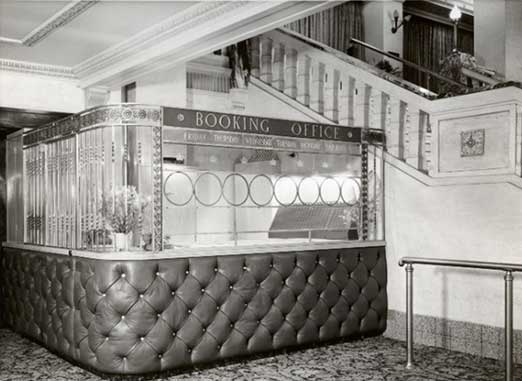

“A social highlight for many, attending the theatre was an occasion for getting dressed up. The interiors of picture theatres echoed the glamour of the films they showed and were designed to create a sense of occasion,” said Dr Collins.

“The main entrance and foyer were integral to this experience with the design including grand staircases, ticket booths, displays of coming attractions, and soda fountains or candy bars.”

“Within the auditorium, the screen was bordered with theatrical curtains, and flanked with coloured lights, fountains, and, in some instances, an organ or orchestra pit.”

“Often, the large expanses of ceiling and walls were decorated with ornamental plasterwork inset with sound, ventilation and lighting. The Regent Theatre in Rundle Mall being a key example of this,” said Dr Collins.

This exhibition also explores what happens when these businesses close down, with examples including the Regent Cinema in Rundle Mall recently given new life as a bookshop, as well as those we have lost to demolition such as the Ozone at Glenelg.

By holding up a mirror to the past and examining our constructed world we can learn not only about the bricks and mortar of cinema buildings but also about the relationships and networks of people who brought them about, how film culture impacted our lives, as well as learning about the wider community which they served.

Now Showing… Cinema Architecture in South Australia

Kerry Packer Civic Gallery – Hawke Building, UniSA City West Campus, 55 North Terrace, Adelaide

Exhibition continues to 30 May 2024

Free entry

For more information, visit: www.unisa.edu.au for details.

Images: Hindmarsh Town Hall (supplied) | Capri Theatre, Goodwood, 1940, Chris A. Smith, Hurren, Langman and James Collection | Renovations of interior, Regent Cinema, Adelaide, 1940 (Ellis Collection)