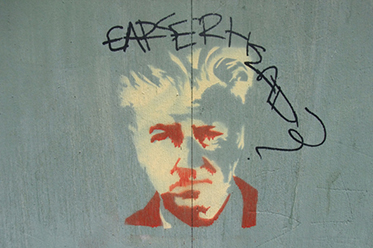

Earlier this month, at the opening of an exhibition dedicated to his work at Brisbane’s GOMA, David Lynch got stuck into street art, calling it “ugly, stupid, and threatening”. Apparently, shooting movies can be very difficult when the building you want to film is covered in graffiti and you don’t want it to be.

Earlier this month, at the opening of an exhibition dedicated to his work at Brisbane’s GOMA, David Lynch got stuck into street art, calling it “ugly, stupid, and threatening”. Apparently, shooting movies can be very difficult when the building you want to film is covered in graffiti and you don’t want it to be.

Is there a distinction between art and vandalism? This is the question that always seems to rise up when graffiti becomes a topic of conversation, as it has after Lynch’s outburst. This is, however, not just important for those of us who want to know the answers to obscure questions such as, “what is art?” It affects everyone. Why? Because graffiti exists in our public spaces, our communities and our streets.

Let’s for a minute put aside the fact that an artist such as David Lynch, known for pushing the envelope in terms of what art is and can be, is criticising one type of art on the grounds that it is inconvenient to the kind of art that he prefers to undertake.

There is something more important to discuss here. The opinion that street art is vandalism (that is, not art) is widely held. Many people despise graffiti – but we are more than happy to line our public spaces with something much more offensive: advertising. That’s the bigger story here, the use and abuse of public space.

At heart, I think this is why people don’t like graffiti. We see it as someone trying to take control of a part of our public space. The problem is, our public spaces are being sold out from under us anyway. If we don’t collectively protect our public spaces, we will lose them.

Two types of graffiti

I would like to make a bold distinction here. I want to draw out the difference between two kinds of graffiti: street art and vandalism. We need something to be able to differentiate between Banksy and the kids who draw neon dicks on the back of a bus shelter. They are different, and the difference lies in their intention.

Tagging, the practice of writing your name or handle in prominent or impressive positions, is akin to a dog marking its territory; it’s a pissing contest. It is also an act of ownership. Genuine street art does not aim at ownership, but at capturing and sharing a concept. Street art adds to public discourse by putting something out into the world; it is the start of a conversation.

The ownership of a space that is ingrained in vandalism is not present in street art. In fact, street art has a way of opening up spaces as public. Street art has a way of inviting participation, something that too few public spaces are even capable of.

Marketing vandals

If vandalism is abhorrent because it attempts to own public space, then advertising is vandalism. The billboards that line our streets, the banner ads on buses, the pop-ups on websites, the ads on our TVs and radios, buy and sell our public spaces. What longer lasting sex? A tasty beverage? To be young, beautiful, carefree, cutting edge, and happy? For only $24.95 (plus postage)!

Advertising privatises our public spaces. Ads are placed out in the public strategically. They are built to coerce, and manipulate. They affect us, whether we want them to or not. But this is not reciprocated.

We cannot in turn change or alter ads, nor can we communicate with the company who is doing the selling. If street art is the beginning of a conversation, advertising is the end. Stop talking, stop thinking – and buy these shoes!

Ads v graffiti

We are affronted by ads. They tell us we are not enough. Not good enough, not pretty enough, not wealthy enough. At its worst, graffiti is mildly insulting and can be aesthetically immature. But at its best, it can be the opening of a communal space: a commentary, a conversation, a concept captured in an image on a wall. Genuine street art aims at this ideal.

At its best, advertising is an effective way of informing the public about products and services. At worst, advertising is a coercive, manipulative form of psychological warfare designed to trick us into buying crap we don’t need with money we don’t have.

What surprises me is that the people who find vandalism in the form of tagging and neon dicks highly offensive have no problem with the uncensored use of our public spaces for the purposes of selling stuff.

What art can do

If art is capable of anything in this world, it is cutting through the dross of everyday existence. Art holds up a mirror to the world so that we can see the absurdity of it. It shows us who we really are, both good and bad, as a community.

Street art has an amazing ability to do this because it exists in our real and everyday world, not vacuum-sealed and shuffled away in a privileged private space. Its very public nature that makes street art unique, powerful, and amazing.

If we as a community can recognise the value in street art, we can begin to address it as a legitimate expression. When we value street art as art, we can engage with it as a community and help to grow it into something beautiful.

When street art has value, our neon dicks stop being a petty and adolescent attempt at ownership, and become mere vandalism. When we value our public spaces as places where the we can share experiences, we will start to see the violence that is advertising as clearly as the dick on the back of a bus shelter.

Not all graffiti is vandalism – let’s rethink the public space debate

By Liam Miller, The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Image: Eraserhead David Lynch Graffiti – zoomar