In a blaze of vertiginous high notes and bel canto craft deployed with seeming effortlessness, Australian soprano Helena Dix gave every bit of her best to a packed Athenaeum Theatre at Sunday’s opening performance of Melbourne Opera’s new production of Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia – not only taking ownership of the title role but eye-openingly reinventing it.

In a blaze of vertiginous high notes and bel canto craft deployed with seeming effortlessness, Australian soprano Helena Dix gave every bit of her best to a packed Athenaeum Theatre at Sunday’s opening performance of Melbourne Opera’s new production of Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia – not only taking ownership of the title role but eye-openingly reinventing it.

UK-based Dix is back in the loving embrace of a local audience familiar with and eager to see the bold and beautiful signature she adorns her characters with. Like the series of formidable but troubled female characters she has studied and brought to life – Melbourne won’t easily forget her imperious Elizabeth I for Melbourne Opera’s Roberto Devereux and fearsome Lady Macbeth – Lucrezia is a natural fit for Dix’s unshrinking presence and superb technique. Dix provides the ultimate drawcard.

And so too does Lucrezia. An infamous noblewoman of the Italian Renaissance, born illegitimate to a family adept at political scheming, Lucrezia’s lasting reputation as a temptress, manipulator and murderess, justified or not, is exactly the woman portrayed in Victor Hugo’s play, Lucrezia Borgia, and which Donizetti and librettist Felice Romani based their 1833 opera on.

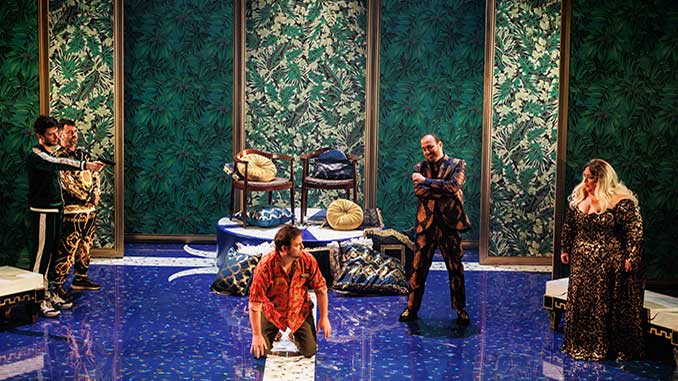

From theatre director Gary Abrahams, whose debut on the opera stage signals exciting work ahead, Renaissance Venice and Ferrara are reborn as places where the gaudiness and glitziness of the lives of a partying, showy and seedy syndicate of mafia-suggested thugs reside.

Abrahams takes the libretto’s poetically and emotionally charged long-winded language and enacts it with a snugly fitting interpretation set in what appears the late 1990s. The energy, detail and intrigue created are constantly felt.

The story goes like this. Lucrezia keeps her identity a secret after having tracked and found her illegitimate son Gennaro, who was raised in a fishing village and never knew her. Complicating matters, Gennaro finds her sexually desirable but learns from his friends that she is no other than the infamous Lucrezia Borgia who has stained their lives in one tragic way or another.

Having overheard their insults, Lucrezia wants revenge on Gennaro’s friends while Don Alfonso, her fourth husband, has suspicions Gennaro is her lover and wants him disposed of. Gennaro is poisoned but saved by an antidote Lucrezia gives him.

Still unaware she is his mother, he joins a party with his best friend Orsini where they are caught up in Lucrezia’s act of poisoning his friends. Finally learning that she is his mother, he refuses to take what little antidote remains and, loyal to his friends, he dies.

Unashamedly melodramatic at its operatic best, one notable aspect makes this Lucrezia stand apart. In the end, despite an intoxicating and emotional outpouring of divinely ornamented urgency and pain in the dizzyingly demanding final aria, Era desso il figlio mio, Dix seemingly refuses to allow any sympathy from her audience for the callous and calculating woman she portrays. Instead, tears might roll during this treasured highlight for Gennaro, holding on dearly to his friend Orsini as both are close to death.

How could sympathy be bestowed? When Dix makes her entrance and Lucrezia first meets Gennaro, she responds to his affections with far more than a mother ought to and crosses boundaries with a wandering hand on her son’s chest and thighs.

Was Lucrezia going along with it in order not to lose him? Dix’s eyes and fingers said otherwise, the first of dozens of cleverly utilised actions and touches she seemingly uses to sculpt a detestable Lucrezia.

Certainly, the spotlight falls dramatically on Dix’s Lucrezia but Donizetti’s powerful music is given some highly commendable vocal treatment by those around her.

What James Egglestone reveals as Gennaro is utterly convincing to see of a young man following his heart in which the love for his unknown mother is large. Egglestone puts his tenor of lively and attractive oaky timbre to good use although, at forte, the top of the voice lost shape and shading on opening night.

Christopher Hillier gives an impressively smooth performance as Lucrezia’s deplorable iron-fisted hubby, Don Alfonso, his toasty and expressive baritone blending wonderfully with Dix and Egglestone.

Mezzo-soprano Dimity Shepherd is a beacon of exuberant life and singing as Orsini in a pants role that endearingly shows Orsini has desires on Gennaro – and it’s not like the text couldn’t be interpreted as such.

Amongst the three-quarters of the soloists losing their lives, some excellent voices rang out in supporting roles. A brief encounter with grand, sonorous bass Eddie Muliaumaseali’i in a cameo as Astolfo sadly comes to a throat-slashing conclusion.

Baritone Christopher Tonkin parades confidently as Gubetta in the service of Lucrezia and Richard Divall Emerging Artist, tenor Alastair Cooper-Golec, is to be praised for his suave and soaring turn as Don Alfonso’s number one young man, Rustighello – both of whom survive.

Not so lucky were Adrian Tamburini as Gazella, Adam Jon as Petrucci, Louis Hurley as Vitellozzo and Christopher Busietta as Liverotto who all, having given a dazzling show of themselves, succumb to Lucrezia’s poison along with Gennaro and Orsini.

The Melbourne Opera Chorus, a predominantly male affair, seize the moment to offer a display of robust and unified proportion while conductor Raymond Lawrence commendably brought out the dramatic finesse and often frenzied intensity of the score, if at times losing orchestral cohesion, from the Melbourne Opera Orchestra.

Reflecting the distaste of circumstances, Harriet Oxley’s costumes convey the setting fabulously with electrifyingly colourful Versace-esque leisurewear and mafioso black suites. Greg Carroll’s panelled sets are deceivingly simple and effective in their suggestion of wealth and power and Niklas Pajanti’s lighting design is meticulously conceived in the way it casts excitement and mood on every scene.

It may or may not be an of-the-moment exaggeration to say that the total creative effect worked quite astonishingly. Dix undoubtedly is not to be missed but her world of Lucrezia is generously enhanced by Melbourne Opera’s bristling and persuasive production.

Lucrezia Borgia

Athenaeum Theatre, 188 Collins Street, Melbourne

Performance: Sunday 28 August 2022

Season continues to 6 September 2022

Bookings: www.ticketek.com.au

For more information, visit: www.melbourneopera.com for details.

Image: Lucrezia Borgia – photo by Robin Halls

Review: Paul Selar