I don’t want to be there when it happens is a multi-media exhibition that attempts to engender empathy within and between communities, cultures, ideologies, and historical frameworks. The works in this exhibition focus upon a distinct sense of unease that exists within our time and place in the world, an existential anxiety concerned with issues of the past and future.

I don’t want to be there when it happens is a multi-media exhibition that attempts to engender empathy within and between communities, cultures, ideologies, and historical frameworks. The works in this exhibition focus upon a distinct sense of unease that exists within our time and place in the world, an existential anxiety concerned with issues of the past and future.

Such anxiety is provoked by increased levels of bigotry and discrimination, based on race, religion, or simple class status – a function of society that one would have assumed disappeared with the Victorian age yet is all too much of a chronic societal problem in today’s day and age.

More specifically, I don’t want to be there when it happens comes in the wake of the 70th anniversary of the Partition of India in 1947, an occurrence that saw a divide of the country, a forced mass migration and, as a result, over a million deaths. The colonial power of Britain departed and the West became Muslim-majority Pakistan, while the majority of people in what has now become India practised Hinduism.

The exhibition focuses on uniting differences, fostering empathy, and creating harmony from disjunction, as well as expressing a deep-seated worry and fear of what is to come and what has been in today’s uncertain and intolerant times. As such, the exhibition features artists from both Pakistan and India in memoriam of the appalling loss of human life.

Many of the works in the exhibition are artistically brilliant and viscerally powerful pieces of work. The imposing and intriguing sculptures of Adeela Suleman, After all it’s always someone else who dies (2017) and I don’t want to be there when it happens (2017), seem at first glance to be expansive and intricate decoration, one as a hanging curtain and the other as a chandelier, yet closer examination reveals the works to be much more than decorative pieces.

The recurring bird-form pattern is intricately hand-beaten, displaying a methodical and dedicated approach, as well as extraordinary artistic skill and attention to detail. Further, the repeating bird pattern refers to the appalling number of deaths that occur in Pakistan due to suicide bombings. Suleman uses a beautiful and ethereal work to refer to an ugly part of her country’s history and, through the otherworldly nature of the work, represents a quiet, unsettled feeling; a pervading sense of worry for the future that underlies the work.

The exhibition unites various cultural myths and folkloric elements, notably in the works of Abdullah M. I. Syed and Raj Kumar. Syed’s work, Flying Rug of Drones (2015-17), is a hanging mobile, consisting of numerous drones, in miniature, made from razor blades. Syed evokes Orientalist myths such as the flying carpet of the Prophet Sulaiman and the “Arabian Nights” to question the Western attitude to Eastern nations, prompting discussions of Islamophobia and extremism.

The work reflects the distance and inhumane nature of drone warfare, by creating a relationship between what is there and what is seen. The work is lit such that stark shadows are cast upon the wall, presenting an image of the drone mobile, while not being the real thing that hangs mysteriously above the viewer.

The work explores distanced attitudes, such xenophobic and extremist beliefs, held by those at a significant remove from any individuals concerned. Through evoking the flat emotionalism and the distance created through the use of drones, the work creates and problematizes the notion of the ‘mysterious other’, a particular facet within postcolonial discourse that typically leads to the repression and discrimination of people by a colonial power.

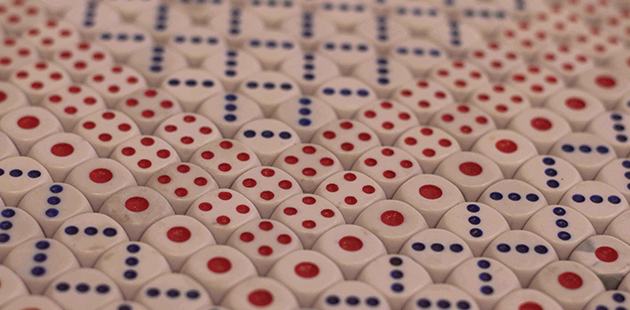

Kumar’s work, Meet, Pray and Play (2016), on the other hand, relates to the complex idea of religion. Kumar creates prayer mats, that at first appear to be intricately woven yet are in reality made of thousands of dice, that are displayed to evoke the architectural splendour of cathedrals and mosques.

Yet the work also brings to mind the legend of the flying carpet and vagrancies of life, noting the entirely chance nature of varying ideologies, belief systems, and cultural values that fundamentally separate entire groups of people yet are entirely dependent upon the random event of being born in one location or another. The work also explores the transiency of life through a reflection of such fundamental belief and value systems as dependent upon chance.

I don’t want to be there when it happens is a highly evocative and successful exhibition, one that unites cultural beliefs, elements of folklore and historical and futuristic worries and occurrences. Yet, while largely a marvel of masterful artistry, the photographic piece Saline Notations (2015) by Reena Saini Kallat, and the video work, Earthwork (2017) by Sonia Leber and David Chesworth, seem to be missing an aspect of the technical ability that makes the rest of the exhibition so outstanding.

While these pieces demonstrate some significant conceptual merit, the technical output appears to be lacking. The piece Earthwork aims to explore the issue of drone pervasiveness and disruption, and consists of a model of a world suffering from drone destruction. The construction used to portray this destroyed world is quite clearly a model, and while that should not make the piece any less poignant or powerful, the reality of my experience with the piece was a distinct lack of feeling.

For such a pressing issue, a work of art ought to make the viewer engage in the work through an emotional connection to the work. Within the context of this exhibition, in conjunction with the other works, the piece was the equivalent of a stocking-filler, being used to bulk out the exhibition.

The work Saline Notations displays a series of photographs portraying the washing away of a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, The Mind is Without Fear (1900), written in white block letters over the sand. Yet such a piece seems to be given prescience through the effect of the “white cube.”

That is, the most basic of technical output is bestowed relevance and poignancy through the inclusion in an art gallery. Art galleries make art. I might question whether the work would be valued quite as highly were it to be shown outside of an art gallery space. The message and the conceptual idea behind the piece, however, is strikingly powerful, representing the rush of freedom from one’s mental chains and the transient nature of art, culture, and human production.

However, despite some blips, this exhibition is an insightful and evocative remembrance of a tragic occasion, and a pressing call to all cultures for the need to build bridges, heal old wounds, and feel empathy for one another, in spite, or perhaps because of, diversity.

I don’t want to be there when it happens

PICA – Perth Cultural Centre, 51 James Street, Northbridge

Exhibition: 11 November – 24 December 2017

For more information, visit: www.pica.org.au for details.

Image: Raj Kumar, Meet, Pray and Play (2016). playing dices – Image courtesy the artist

Review: Karl Sagrabb