For a prime example of Australia’s innovation economy in action, look no further than the humble picture book. Staple of bedtime reading, offering textual delights beyond the verbal, picture books are a hidden treasure.

For a prime example of Australia’s innovation economy in action, look no further than the humble picture book. Staple of bedtime reading, offering textual delights beyond the verbal, picture books are a hidden treasure.

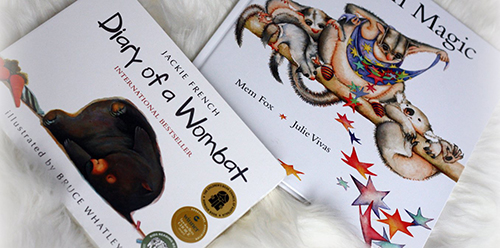

Australian picture books sell around the world, and are translated into many languages – take for instance, Jackie French’s iconic Diary of a Wombat (2002), which appears in French, German, Korean, and many more. But though the words need translating, the images, (in French’s book by Bruce Whatley), communicate across language barriers.

The interplay between words and images is one of the magic ingredients in a show-stopping picture book. Achieving that magic requires serious innovation. Writers, illustrators and editors work hard to balance word with image, and to carry the story or message through both.

It takes time, dedication, and care to make a picture book, and though some may be flipped through in minutes, others repay repeated reading and looking. Next time you pick one up in a bookshop or library, look at its design, the way the pictures engage with character, or setting, or contribute to mood, theme, and the controlling idea.

Ann James’s illustration of I’m a Dirty Dinosaur (2013) (text Janeen Brian) is a recent example. James’s lively dinosaur invites children into the story, acting out the rhymes:

I’m a dirty dinosaur

with a dirty snout.

I never wipe it clean

I just sniff and snuff about.

Simple but evocative line drawings of this muddy dinosaur (made using Victorian mud!) connect beautifully with the energy of the rhymes, and provide young readers with visually engaging and memorable ideas.

Kevin Burgemeestre’s wonderful handmade dioramas on the cover of the recent Hush Treasure Book (2015) show that illustrations don’t have to be drawn to be lively and vivid. Indeed, in another of his books, B is for Bravo (2003), they provide a realistic but imaginative romp through an excitingly three-dimensional alphabet of Australian Aviation.

Illustrators conduct specific research to find just the right images for particular stories. Anne Spudvilas’s illustrations for the picture book version of Li Cunxin’s Mao’s Last Dancer (2003) use traditional watercolour, and collage from old newspapers, to convey the wealth and variety of Chinese culture.

Experimentation, consultation, imagination, teamwork and individual interpretation are the name of the game. And they demonstrate the incredible care writers and illustrators take to make books that speak to the text, and to the reader. You can see Ann James talk here about how she conveys emotion in collaboration with the author:

Jeannie Baker, meanwhile, takes collage to its highest level in her carefully crafted books. Her Window (1991), and Where the Forest Meets the Sea (1987) use layered and detailed images and to convey a powerful environmental message.

Sometimes words are unnecessary. Shaun Tan’s The Arrival (2007) tells a moving story about immigration through sepia pictures arranged as if in an old photo album. Any words would break the spell cast by these pictures, which call for a slow and thoughtful reading. Indeed, the only words that appear in the book are in a made-up font. Their unrecognisability symbolises the challenges facing new immigrants who have yet to learn the local language.

Gregory Rogers’s comic wordless story The Boy, the Bear, the Baron, the Bard (2004) is a wonderful contrast. Full of pace, fun, and historical detail, in company with the boy, bear and baron of the title, it takes us through the streets and theatres of Elizabethan London, pursued by the bard.

Exact statistics as to the number of Australian illustrators are hard to come by: like authors, they receive royalties of up to 10% (sharing this figure, in the case of co-creation). And so, like so many creatives, to survive and flourish they have to be extremely energetic, professional and passionate about their work. To survive, they have had to innovate.

Publishing opportunities are increasingly competitive, as the digital economy hits traditional publishers, though the development of the app-book offers new and interesting opportunities.And Nick Bland challenges the form of the picture book altogether, with The Wrong Book (2009), in which monsters, pirates, royalty and animals intrude on the protagonist’s attempts to tell a story. (It’s available as a lovely app)

Many illustrators give classes, workshops, do school visits, are part of exhibitions, and support literacy initiatives at home and abroad. They find new ways to promote their work, and cross-fertilise with other industries.

I’ve only touched on a few of the many wonderful Australian creators of picture books for young (and not so young) readers. Next time you read one (to yourself or to others), you could think about the innovation economy that is the illustration industry. But hopefully, and more likely, you could settle back and enjoy the story – words, images, and all.

This week is Children’s Book Week. And the Children’s Book Council of Australia will announce a swag of prizes in various award categories, including picture books. The University of New England has hosted many illustrators over the years through a Copyright Agency Cultural Fund supported residency program. The work they did is on display at the University Library.

How Australia’s children’s authors create magic on a page

Elizabeth Hale, Senior Lecturer in English and Writing (children’s literature), University of New England

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Image: scribbletaylor / flickr, CC BY-NC