Australia’s performing artists are ageing and facing increasing poverty, poor health, homelessness and depression, with attempted suicide rates more than double the general population, according to the confronting new Platform Paper from Currency House.

Australia’s performing artists are ageing and facing increasing poverty, poor health, homelessness and depression, with attempted suicide rates more than double the general population, according to the confronting new Platform Paper from Currency House.

In Falling Through The Gaps: Our artists’ health and welfare, author Dr Mark R.W. Williams, a prominent arts & entertainment lawyer, argues government industry services – in assuming purely monetary economic rationalism as the motive for all Australians – discriminate against those in specialised vocations who devote their lives to perfecting their craft.

With kind permission of Dr Williams and Currency House, Australian Arts Review publishes the following extract:

Falling Through The Gaps: Our artists’ health and welfare – Dr Mark R.W. Williams

Early in my discussions, various actors said words to this effect:

I’m a household name and recognised internationally, thanks to my regular appearance over several series on television or for up to twenty years in a regular role. I might not be in every episode but I will be in running storylines. My character has grown up, been promoted, developed a backstory but, at most, it amounts to two weeks’ work. Sometimes all my scenes will be shot in one day. I’m scratching for work the other fifty weeks of the year. When people tell me my reputation has never been higher, I’ll tell them my bank balance has never been lower.[i]

The point is not to re-hash the plot of Singin’ in the Rain or the more recent Oscar-winning The Artist, in which one actor is put out to pasture by the advent of new technology. What I am saying is that there will always be casualties of technological change. What we have seen since the advent of free-to-air television, slow as it was to arrive in Australia, is that yet another generation of performers is approaching poverty; but this time it is occurring even whilst their services are still firmly in demand.

All other costs have grown and in-built ‘cost disease’ continues to apply to theatrical content.[ii] In reality performers have absorbed the pressure to offer their day-to-day services for less and less. This is not just less and less money, it is also fewer working hours and longer working lives eking out smaller rewards.

No sole-trader actor can afford to let their brand slip into obscurity by declaring themselves to be unemployed or retired; but the reality in Australia is that, no matter what unique skills, experience, awards and honours a professional performer may hold by mid or late career, most are underemployed or spend long periods ‘resting’, developing new work or, indeed, waiting to get paid for jobs.

All of these factors are treated individually by the industrial relations, tax, social security and arts-funding mechanisms. The problem has been recognised for well over a generation but no one has yet been able to harmonise the systems.[iii] In this regards, whilst my concentration is on actors, most other workers in artistic pursuits—and many another freelancer—face similar structural problems: their reality does not conform to those of the nominal Australian workforce.

At the centre of the way actors are engaged is an idiosyncrasy which, to my lawyer’s eye reveals a long-standing structural ambiguity. The Live Performance Award and the Actors’ (Theatrical) Award which preceded it and the equivalent film and television awards, contain the apparently innocuous requirement that an individual contract be entered with each performer. The contract includes minimum provisions such as identification of the length of engagement, breakdown into rehearsals and performances and so on, which reflect variables not covered by the award. Other industrial awards don’t need to do this.

Short-term ‘contracts’—even though the relationship is one of employment in the professional theatre—is a structural assumption. Many actors’ tasks are not mentioned in the contract or in the award at all, such as the time required to learn parts, pre-production meetings with directors and designers and a myriad of other criteria which are left to ‘the custom of the industry’, arrangements with agents or individual house style.

The reality is that, even when employed, actors are on their own in a way that is quite different from employees in other industries in steady employment. The structural ambiguity reflects the fact that an unambiguous employment relationship is far from the norm for actors and other freelancers working in the performing arts. This flows through to ambiguities in taxation and eligibility for grants and other support from government, but the first problem confronting most workers in the performing arts in between engagements is the need to seek income support.

Governments of all persuasions seek to reduce the official unemployment statistics. Most research that I am aware of stresses that gainful employment is better than no employment for health, mental health and, of course, the bank balance. Our present unemployment benefit system is directed to those goals. It has become progressively more difficult to mesh freelance work and the intermittent opportunities of the performing arts with such a regime.

Mark RW Williams is a Melbourne-based solicitor working in copyright law, particularly as it applies to the creative sectors. He is Adjunct Professor in the School of Arts at RMIT University and a Committee Member of the Victorian Actors’ Benevolent Trust: www.vabt.com.au

Falling Through the Gaps: Our artists’ health and welfare is published by Currency House as Platform Paper No. 56 and is available at: www.currencyhouse.org.au

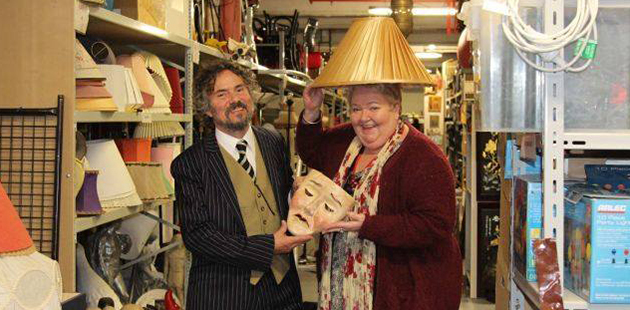

Image: Dr Mark R.W. Williams with Sally-Anne Upton, President, Victorian Actors’ Benevolent Trust – courtesy of VABT

[i] Personal communications.

[ii] The ‘cost disease’ in the arts is a whole topic in itself. Put simply, increased productivity has its limits: you cannot perform a string quartet with two players doing the work of four, though that is precisely what we see today down in the pit of big stage musicals where the musical director is also playing multiple keyboards.

A select bibliography might include William J Baumol, and Harold Bowen, The Performing Arts: The Economic Dilemma (New York: Twentieth Century Fund) 1966; David Throsby and Glenn Withers The Economics of the Performing Arts (London: Edward Arnold) 1979; Ruth Towse Baumol’s Cost Disease, The Arts and Other Victims (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar) 1997.

[iii] The then Federal Shadow Arts Minister, Peter Garrett, announced a proposal, ArtStart, to harmonise criteria for artists across government and address perennial financial sustainability problems. http://www.chass.org.au/media-releases/labor-announces-its-vision-for-the-arts/ It was Labor’s New Directions for the Arts policy associated with the successful 2007 election campaign. Once in government it morphed into a grant scheme analogous to the New Enterprise Initiative Scheme (NEIS).