The world premiere exhibition of Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives has opened at Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum, where ancient cultures meet modern technologies, taking audiences beyond the wrappings to reveal the mysteries of mummification buried for thousands of years.

The world premiere exhibition of Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives has opened at Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum, where ancient cultures meet modern technologies, taking audiences beyond the wrappings to reveal the mysteries of mummification buried for thousands of years.

The six mummies from the British Museum collection, who lived and died in Egypt between 1800 and 3000 years ago, were scanned at Royal Brompton Hospital in London. They will be displayed in their historical, geographical and social contexts alongside 200 objects exploring themes such as mummification, gods and goddesses, personal adornment, state of health and medicine, food and diet, musical instruments, and childhood.

Australian audiences will have a chance to see inside mummies, virtually peeling back the layers of history via the latest non-evasive computed tomography (CT) scan and 3D visualisation technology to discover for themselves six carefully mummified individuals.

“This is a rare opportunity to get a close-up look at the mummies of the British Museum,” said Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS) Director, Dolla Merrillees. “They are in exceptional condition and now, thanks to modern technology, we are able to uncover their stories and secrets while preserving their dignity and leaving them intact. With a combination of Egyptian history and interactive science, Egyptian Mummies is the ideal family exhibition this summer.”

The six mummies on display in Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives include:

Nestawedjat – The name Nestawedjat is inscribed in hieroglyphs on each coffin and, as with most ancient Egyptian names, it has a meaning: The one who belongs to the wedjat eye. The style and the quality of her coffins suggest that she came from Thebes (modern Luxor), a major religious centre in ancient Egypt. A married woman, she belonged to a wealthy family. This is confirmed by her carefully mummified body, which provides an excellent example of ancient Egyptian mummification.

Tamut – Inscriptions on her case identify Tamut as the daughter of Khonsumose, a priest of the god Amun, king of the gods. As members of a high-status family, Tamut and her father would have taken part in rituals in the temple of Karnak, the most important religious complex at Thebes (modern Luxor). Tamut’s mummy illustrates how preservation of the body was only one element of the ancient Egyptian response to death.

Irthorru – lived in the town of Akhmim, situated about 200 km north of Thebes (modern Luxor). The inscriptions on his finely decorated coffin tell us his name and role – like many of his relatives, Irthorru was a priest. Serving several gods, he probably divided his time between different temples, including that of the fertility god Min whose cult flourished at Akhmim.

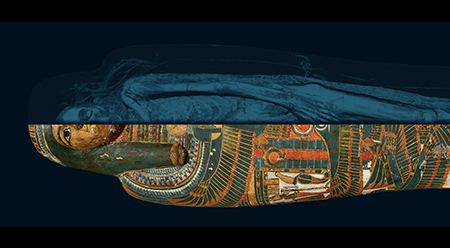

Temple Singer – Although we do not know her name, the inscription on this woman’s cartonnage case tells us that she was a priestess – more precisely a Singer of the Interior of Amun. She lived in Thebes around 800 BC and probably worked at the temple of Karnak. We have no record of her personal life, but being a priestess would not have prevented her from marrying. CT scans show that she was probably between 35 and 49 years old when she died and suffered from various dental problems – one of her front teeth is missing.

A young child from the Roman Period – In ancient Egypt few children appear to have been mummified. However, during the Roman period the practice seems to have increased and many examples have been uncovered at the cemetery at Hawara. CT scans confirm that the boy was around two years old when he died. His spine and ribs were damaged, possibly during mummification, but his body was wrapped with great care in many layers of bandages. His gilded and finely decorated cartonnage mask suggests that he came from an elite family.

A young man from Roman Egypt – Mummification continued to be practised when Roman rulers took over Egypt in 30 BC. However, the techniques and styles used in mummification evolved during this period. One major innovation was the use of wooden panels depicting the deceased, known as ‘mummy portraits’. The picture shows a young man with dark curly hair, thick eyebrows and wide eyes. He is beardless, indicating youth, and CT scans have confirmed that he was between 17 and 20 years old when he died.

“Egyptian Mummies is a unique opportunity to discover more about life and death in ancient Egypt,” said Co-Curator of the exhibition, Project Curator at the British Museum and Egyptologist, Marie Vandenbeusch. “British Museum’s curators, scientists and conservators combined their knowledge to explore CT scan data and study objects from the museum’s vast collection, providing a unique insight into the life of six ancient individuals.”

Join some of Australia’s leading and emerging Egyptologists as they reveal the history behind Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives in a regular series of object focused talks, which delve into specific aspects of ancient Egyptian history, including language, religion, funerary practices, art and architecture, health and medicine and the history of mummy studies. There will also be curator tours and expert talks from Macquarie University and the Australian Centre for Egyptology revealing the science behind archaeological practices and CT scanning techniques.

Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives

Powerhouse Museum, 500 Harris St, Ultimo (Sydney)

Exhibition continues to 25 April 2017

Information and bookings: maas.museum

Image: Temple Singer with scan – © Trustees of the British Museum