In his budget reply speech in May, Bill Shorten claimed that “coding is the literacy of the 21st century.” With the possibility of technology taking over our jobs, now is the perfect time to remind ourselves of the value of Australian craft culture, and the beauty of the handmade.

In his budget reply speech in May, Bill Shorten claimed that “coding is the literacy of the 21st century.” With the possibility of technology taking over our jobs, now is the perfect time to remind ourselves of the value of Australian craft culture, and the beauty of the handmade.

In September, Melbourne will host the inaugural Radiant Pavilion, an international jewellery festival – along with the state organisation’s Craft Cubed and national conference, Parallels: Journeys into Contemporary Making – to be delivered by the National Gallery of Victoria.

This conference culminates the National Craft Initiative (NCI), managed by the National Association of the Visual Arts (NAVA). A 2014 report by the NCI, Mapping the Australian Craft Sector, called for an urgent review of its sustainability.

Craft appreciation

In 2009 NAVA Director Tamara Winikoff described craft in the community in the following terms:

The extent of the Australian community’s engagement with craft and design (over 2 million participants) is a powerful affirmation of the deep seated satisfaction which people gain from the exercise of their imagination and skill. The ambition of the NCI is to stimulate engagement of the Australian craft and design sector with new ideas, ways of doing things, connections and opportunities.

University of South Australia’s Susan Luckman’s recent book, Craft and the Creative Economy (2015), reflects on the growing interest in the handmade, prompted by increasing awareness of exploitation in global industrial production:

Craft, as both objects and process, appeals in this moment of increasing environmental and labour awareness as an ethical alternative to mass-production; craft also speaks to deep human connections to, and interest in, making and the handmade as offering something seemingly authentic in a seemingly inauthentic world.

The internet – bringing with it businesses like etsy.com, which has exceeded US$2 billion in transactions – promises to extend the intimacy of the local market to a global audience, offering a sense of connection that is lacking elsewhere. But how does Australia feature in the global industry of craft? Surprisingly, Australia was once a world leader.

The birth and death of craft in Australia

The Crafts Council of Australia emerged in 1964 as a response to an invitation from the World Crafts Council (WCC) to attend its inaugural event in New York. In 1973, the Crafts Board was established to represent the arts in the Australia Council alongside visual arts, dance and literature.

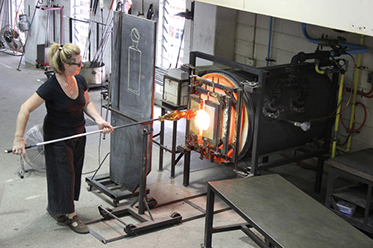

Then in 1980, Australian ceramist Marea Gazzard was the first elected president of the WCC. Political leaders of the time sought to identify with popular crafts, such as Democrats founder Don Dunstan opening the Adelaide’s JamFactory Craft Centre in 1973 and Rupert Hamer launching Victoria’s Meat Market Crafts Centre in 1977.

However, Australian craft has since virtually disappeared from the national stage. Through the 1980s, the Crafts Board was incorporated into the Visual Arts/Crafts Board, and eventually merged into the Visual Arts Board in the 1990s, as it now remains. Finally, the last national link to craft was lost with the 2011 decision to cut funding for Craft Australia.

Recent political leaders have failed to use Australian crafts to demonstrate their national pride, with the exception of John Madigan and Nick Xenophon’s failed attempt to furnish Parliament House with Australian-made crockery.

The now corporatised state-based crafts councils such as Craft Victoria and Adelaide’s dynamic Jam Factory generate much local activity, but they are not supported by a national platform or funding.

Australia’s impact on the global handmade footprint

Though Australian craft is rarely seen on our national stage, we have actually made many unique objects of enduring value. As a material art, craft expresses in a tangible appreciation of the land. Using Japanese techniques, Australian ceramicists give artistic expression to the rich soils, glazed with ash from our native timbers.

As shown in this year’s Venice Biennale, Aboriginal communities from central Australia use the unique plants of the desert to tell sacred stories in fibre sculptures. Wood craftspersons are learning how to adapt European techniques to the challenges of our indigenous timbers. Jewellers have taken the egalitarian approach to materials and learnt how to make exquisite works out of humble materials.

While other nations have attempted to re-focus on making things, the “lucky country” has come to depend more on what can be extracted from the land than is produced on it. The “clever country” imagined during the Hawke-Keating years made a virtue out of the loss of manufacturing, heralding a knowledge economy that focused on financial and education services.

The craftiness of the rest of the world

In the US, President Obama personally hosted the annual Maker Faire last year, reviving some national pride in making things through local production, featuring neighbourhood labs that offer services such as 3D printing. In the UK, craft contributes A$6.5 billion to the economy. The Crafts Council actively presents craft in the public eye, including a recent manifesto – Our Future is in the Making – launched in the House of Commons to promote craft in education.

Across the sea, the Crafts Council of Ireland receives annually A$5.2 million in government funding to support craft initiatives such as Future Makers to nurture the next generation (a per capita equivalent in Australia would be A$26 million for a national craft organisation).

China, South Korea, Japan and India have also dedicated significant funding, international festivals, infrastructure and craftsman support services) to the development and sustainability of locally crafted goods, including Nahendra Modi’s personal commitment to support khadi (handloom) cotton production. But with the end of the mining boom, we are looking at the impact that this loss of productive capacity has on our ability to sustain our future. What exactly will be the legacy of our good fortune apart from large holes in the ground?

The craft of the future

This year – will it be a turning point, or could it be more of the same? For the past two decades, the cult of the new prevented us from building on the unique traditions we have established. Arts talk today is infected with corporate phrases such as “disruptive technologies”, “breaking down barriers”, and “design thinking”.

The obsession to break with the past weakens the social and community values that underpin meaning. Understanding where we have come from offers a trajectory that can guide us into the future. According to Marian Hosking, President of the newly revived World Crafts Council – Australia:

Today’s craftsperson draws on both traditional craft practice and new technologies, with an understanding of historic and social precedence.

The end of the mining boom is a chance to review the implicit direction of Australia as a nation. What will happen as Asian countries inevitably raise their wages, develop first rate universities and create their own designs? Crafts help us answer that question. Crafts demonstrate that we know our place in the world and are committed to make something from it.

Craft in Australia: let’s not forget the real value of the handmade

Kevin Murray is Adjunct Professor at RMIT University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Image: Glass Blowing at Adelaide’s JamFactory