Australian circus is in demand. Contemporary circus and circus-infused physical theatre are amongst our most innovative and sought after cultural exports. Internationally touring companies such as Circa, Strange Fruit, Stalker, and Legs on the Wall have evolved a uniquely Australian blend of circus, physical theatre, and visual language, that is recognised as a particular strength of Australia’s cultural market.

Australian circus is in demand. Contemporary circus and circus-infused physical theatre are amongst our most innovative and sought after cultural exports. Internationally touring companies such as Circa, Strange Fruit, Stalker, and Legs on the Wall have evolved a uniquely Australian blend of circus, physical theatre, and visual language, that is recognised as a particular strength of Australia’s cultural market.

On the domestic arts front, the term ‘circus’ has in recent years finally become a discrete genre category on our major arts festival programs. Physical risk-taking and bold aesthetics, often matched with hot-topic social or political concerns, are part of Australia’s cultural history, and contemporary circuses continue that tradition.

Circus as political commentary

Consider for example Legs on the Wall’s aerial performers scaling the 100 metre AMP skyscraper at Circular Quay in Homeland (2000). Threaded through with themes of migration, rootlessness, and diaspora, the show’s aerial artists ‘walked’ eerily in space as they descended from the top of the tower, evoking the risky uncertainty faced by people who leave their homeland in the hopes of a better future in another country.

Or we might consider Stalker’s Incognita (2003). Set in a seared, post-bush fire landscape, blending skill-sets and apparatus from dance and contemporary circus, the characters of the piece “struggle to survive a buried past, shaped by generations who have feared they will never be at peace in this land.”

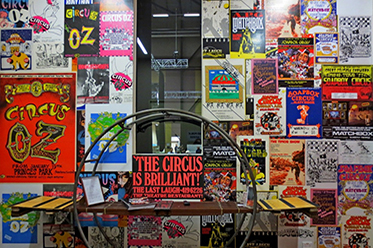

Circus Oz, Australia’s veteran innovator of the circus form, emerged from the politically driven community arts movement in the late-1970s. A left-wing political agenda was a key element of its shows.

After 37 years of operation, Circus Oz is nowadays much loved and enthusiastically funded. Whilst the political agenda of their shows has considerably toned down from the 1970s and 1980s, politics and social concerns continue to inflect their comic, high-energy, family-friendly productions.

FitzGerald Brothers’ Circus

The Australian public’s attraction to circus is not new, and neither is the Australian circus’s interest in high profile social and political issues. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the circus mattered to Australians.

When in Sydney or Melbourne, the largest circus of the era, the FitzGerald Brothers’ Circus entertained audiences in a tent seating 6,000. Although the population of each city was under 300,000, the company’s seasons lasted upwards of six weeks.

The FitzGeralds became nationally famous during the depression years of the early 1890s following two hugely successful seasons in Melbourne (1892) and Sydney (1893). Part of this popularity was their patriotic appeal, as an all-Australian show bursting with Aussie values like pluck, camaraderie and enterprise. Their popularity helped cement these virtues in the emerging national identity.

In 1901, the year of Federation, the FitzGeralds built a permanent circus building at the centre of the country’s new political capital, Melbourne (on the site of the Victorian Arts Centre).

The paradox of performance and propaganda

Over the course of their career, the FitzGeralds created a variety of marketing narratives. Reflecting the complex nature of Australian citizenship, they promoted nationalist ideals such as Australian performers for Australian audiences.

At other times – for example, during the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 – their acts jingoistically advocated Australia’s role as Britain’s imperial partner in the Pacific.

For much of their career the FitzGeralds cultivated the image of their organisation as a pillar of middle-class values, eventually proposing their success as a metonym for the late colonial story of progress. Yet their performances also contravened prevailing cultural mores and challenged normative codes of identity.

Scantily clad female performers, and cross-dressed aerialists, equestrians, and jugglers all starred in their ring, alongside Aboriginal performers and Japanese Sumo wrestlers.

The community of performers and workers on the circus site represented many races – Aboriginal, English, German, Maori, Japanese, Malay. Throughout the years when the White Australia Policy was under construction, the FitzGerald Brothers’ Circus was a genuinely heterogeneous community of many races; a living, working, fully functional alternative to the ideology of one nation, one race.

The FitzGeralds were amongst Australia’s early cultural exports, historical precursors to this country’s leading contemporary circus and physical theatre companies. In the first phase of globalisation (1850-1914), they embraced the principles of cosmopolitanism – the process of developing international networks for the transference of culture and ideas.

Through these cross-cultural and transnational encounters, they introduced Australians and New Zealanders to popular entertainment trends as they emerged in the major centres of the northern hemisphere. They also toured their uniquely Australian version of the circus to international audiences.

For the FitzGeralds, as for some of Australia’s leading contemporary performance companies, politics strengthens the social function of circus.

Gillian Arrighi is the author of The FitzGerald Brothers’ Circus: Spectacle, Identity and Nationhood at the Australian Circus, published by Australian Scholarly Publishing.

Circus and politics: a very Australian mix

Gillian Arrighi, Senior Lecturer in Creative and Performing Arts, University of Newcastle

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.