With this week’s announcement of the winner of the Man Booker International Prize shortlist, translation again finds itself in the foreground of the literary landscape. This year’s shortlist includes novels translated from a diverse array of languages including Arabic (Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi), Hungarian (László Krasznahorkai’s The World Goes On) and Korean (The White Book by Han Kang).

With this week’s announcement of the winner of the Man Booker International Prize shortlist, translation again finds itself in the foreground of the literary landscape. This year’s shortlist includes novels translated from a diverse array of languages including Arabic (Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi), Hungarian (László Krasznahorkai’s The World Goes On) and Korean (The White Book by Han Kang).

In 2016, the prize evolved from a biennial event, designed to honour one living author’s overall contribution to fiction on the world stage, to a yearly prize for fiction in translation. In Australia, too, literary translation is experiencing something of a moment. Shokoofeh Azar’s The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree, translated from Farsi, was recently shortlisted for the Stella Prize.

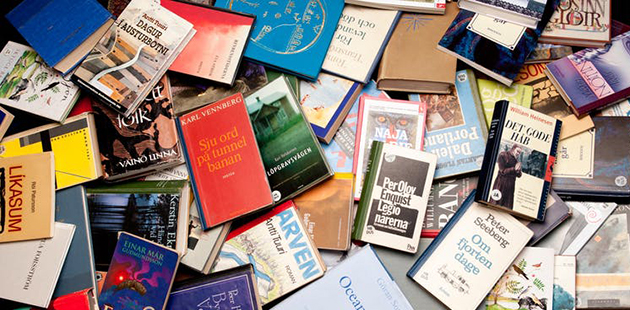

While Europe remains the overwhelming source of translated fiction in Australia, European writing is no longer restricted to classics and bestsellers. Scandinavian crime thrillers are still reliable favourites, but we are also seeing a greater range of Scandinavian literary fiction in translation, alongside relatively underrepresented European languages like Polish and Hungarian. Witold Szablowski’s Dancing Bears (translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones) and Péter Gárdos’s Fever at Dawn (translated by Liz Szász) are outstanding recent examples of the latter.

There are also more works of Asian, Middle Eastern and Latin American literature emerging in translation: Un-su Kim’s forthcoming novel The Plotters, translated by Sora Kim-Russell; Nir Baram’s A Land Without Borders, translated by Jessica Cohen; and Chris Andrews’s forthcoming translation of Marcelo Cohen’s Melodrome, to name just a few.

This suggests the growing openness of Australian readerships towards the rich cultural imaginations of the most intensely othered parts of the world. Literary connections with places like these also link Australia more closely to the experiences of its growing migrant communities.

The translation turn

Two decades ago, translation scholars Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere argued that, as a result of the “coming of age” of translation studies and cultural studies, both disciplines had shifted away from their “Eurocentric beginnings” towards “a new internationalist phase”. Since then, reading cultures across the English-speaking world have taken a similar turn, embracing and engaging with translated literature as never before.

In 2018 the rights to Brow Books’ first translated title – the short fiction collection Apple and Knife, written by Indonesian-born Intan Paramaditha and translated by New Zealand scholar Stephen Epstein – were sold to Harvill Secker, an imprint of Random House UK, demonstrating that Australian translations have global appeal, too.

In Australia, small and independent presses have been leading the charge. Brow Books, the new books imprint of Melbourne literary magazine The Lifted Brow, recently announced a co-publishing agreement with UK-based publisher Tilted Axis Press. Brow Books will be kicking off the partnership in August with the Australian publication of South Korean novelist Han Yujoo’s The Impossible Fairytale (translated by Janet Hong).

Other, more established independent presses have strengthened their commitment to translated literature in recent years. Text Publishing is a mainstay of literary translation in Australia, and is the local publisher of two titles on this year’s Man Booker International longlist: Wu Ming-Yi’s The Stolen Bicycle and Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights (the latter has been shortlisted for the prize).

Text also publishes acclaimed international authors like Herman Koch, Yuri Herrera and Marie Darrieussecq, and has been known to dabble in popular psychology, memoir, and other non-fiction genres in translation.

Melbourne and London-based Scribe and Sydney-based Giramondo have both made strides in publishing translated literature. With the launch of Giramondo’s new Southern Latitudes series, devoted to writers from the southern hemisphere, it is set to publish more Latin American work in translation in coming years.

The fact is, Australians are reading – and publishing – literature in translation, and their tastes are broader than ever. Indeed, in the face of mounting political isolationism, translated fiction might just be the thing to save us. Translation provides a kind of window (if a temporary and sometimes foggy one) onto the experiences and imaginations of people we would never normally have the chance to observe.

What emerges from this snapshot of the literary translation scene, both here and abroad, is the crucial role played by small and independent presses. Such publishers are the lifeblood of marginal, challenging and “unprofitable” literature, whether local or international.

These books give us a glimpse of lives just as real and complex and miserable and beautiful, imaginations just as vivid and dark and brilliant and playful as our own. If Australians are reading more widely, this can only be a good thing.

Australia’s taste for translated literature is getting broader, and that’s a good thing

Alice Whitmore, Assistant lecturer, Monash University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.